Let the Horse Decide: Fuller's Music Story

NBHS Historian/Claudia Houston

At a fork on a sandy road outside Bridgeton, a wagon creaked to a halt. George Reid Fuller Sr., with a pump organ in tow and a horse out front, loosened the reins and let fate—or rather, the horse—choose the way. Left meant Vanceboro; right meant Pamlico County. The horse stepped right, and by nightfall, George had found a kind farmer in Arapahoe who offered him a place to sleep. By morning, the farmer had purchased the organ. It was George’s first sale, and so began a New Bern institution.

George was from the small town of Wilcox, Georgia, and at age sixteen, headed to Savannah, where he was hired to peddle pump organs by horse and wagon from town to town. He soon decided to go into business for himself. On a trip through the mountains, he unfolded a map, spotted the twin rivers on North Carolina’s coast, and decided: if the hunting and fishing were good, business would be, too. He headed east to set down roots.

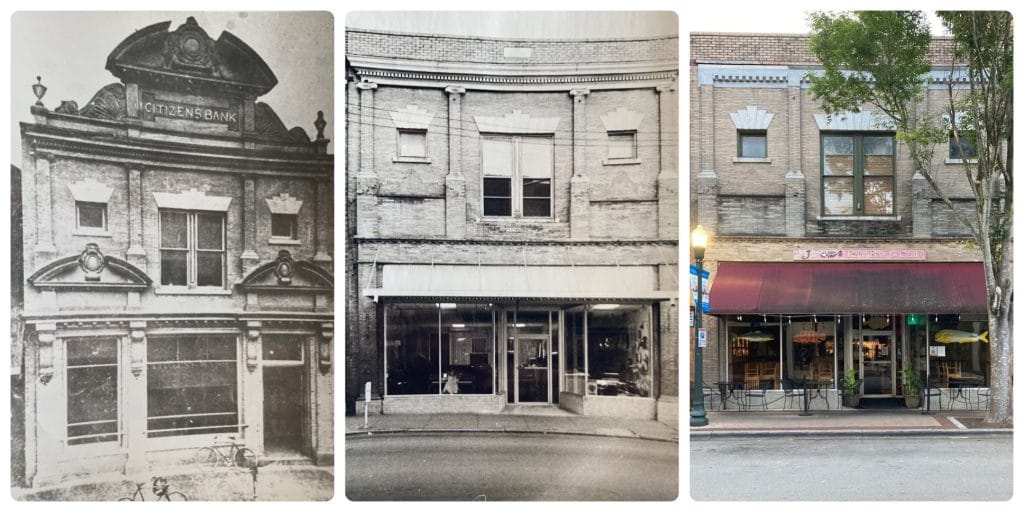

In the early days, George rented retail space at three locations in New Bern while continuing to sell pump organs from his wagon. When the last landlord raised the rent beyond reason, he resolved to buy a building. Local banks turned him away, but a lender in Richmond, Virginia, said yes. To make the down payment, George sold his home. In 1924, Fuller Music moved into the Citizens Bank Building at 216 Middle Street—showroom downstairs, family apartment upstairs—where it remained for the next 75 years. Today, the space is home to MJ’s Raw Bar & Grille.

Fuller’s Music House began on September 5, 1905. George built and sustained his business through the Great Depression, one of only three music stores in the region to endure. Over time, Fuller Music became the oldest continuously operating music store in North Carolina. This year, they celebrated their 120th anniversary in business.

Ever the innovator, George continually refreshed the showroom with modern products. He added player pianos as they became popular, then Victrolas and records, and later TVs. He offered payment plans to keep music within reach for families.

He soon traded hooves for horsepower. In 1914, George bought New Bern’s first Model T and had the rear modified to carry a piano—the town’s first regulation four-wheeled delivery truck. If you ordered an instrument, Fuller would find a way to deliver it. Wade Fuller, George’s grandson and the store’s third-generation owner, tells of a piano sold to a family on Harker’s Island back when there was no bridge, just a mailboat that came once a day. George rode out with the instrument, only to find no dock upon arrival. A handful of burly men waded into the tide, hoisted the piano, and carried it ashore to the designated house. Delivery complete.

Fuller Music’s legacy is also a family one. His older son, George Reid Fuller Jr., known as Reid, joined the business. George Sr.’s youngest son, Andrew, joined his father and brother after returning home from serving as a bomber and fighter pilot with the 8th Air Force in World War II. When George Sr. died in 1957, Andrew and Reid ran the store together. In 1973, Andrew’s son, Wade, came aboard; he later acquired his father’s share in 1976, and his uncle’s in 1981, guiding the business through changing tastes, technologies, and generations of music students.

As New Bern grew, so did the store’s needs. Fuller’s Music built and moved to a new building in 2001at 2310 Trent Road. The new space offered room for a larger showroom, lesson studios, and proper storage—everything a community music hub requires. In January 2016, longtime employee David Rhodes purchased the business, carrying the tradition forward.

From wagon tracks to mailboats to a customized Model T, Fuller Music’s story is one of perseverance, ingenuity, and community. More than a century later, the notes still ring out across New Bern’s twin rivers, where George Reid Fuller Sr. found a new home—and created a legacy.