New Bern's Historical Markers

Explore New Bern's rich and diverse history by viewing our many historical markers located throughout the historical districts and in neighboring James City. With over 1500 historical markers throughout the Tar Heel State, North Carolina's Historical Marker Program is one of the oldest such programs in continuous operation in the United States. To access an overview map of all of the markers, click HERE. For information and the location of New Bern's local markers, click on the individual markers below.

C-1 John Wright Stanley House| 301 George Street

C-2 Tryon Palace | 701 Broad Street

C-3 First Printing Press in North Carolina | 302 Broad Street

C-5 Abner Nash | State Road 1146, James City

C-6 William Gaston | 300 Broad Street

C-7 Richard Dobbs Spaight Marker | State Route 1146, James City, NC

C-10 Baron von Graffenried | 403 East Front Street

C-11 Battle of New Bern | US 70 East at Taberna Way

C-12 Fort Totten | 1402 Trent Blvd

C-14 George E. Badger | 407 Broad Street

C-19 George Washington's Southern Tour | 708 Pollock Street

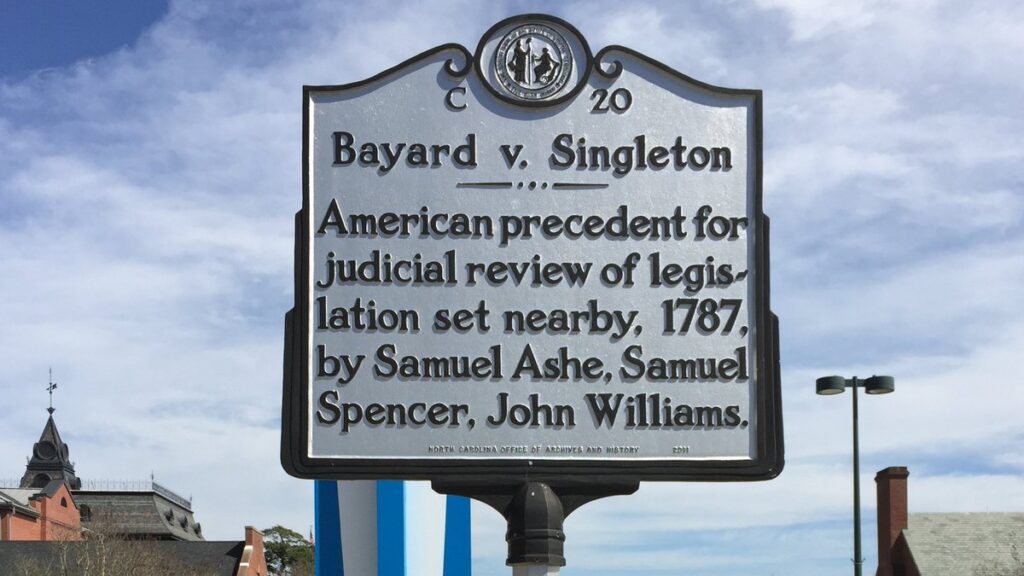

C-20 Bayard v Singleton | 320 Broad Street

C-22 First Post Road | 500 East Front Street

C-25 Fort Point | Old Cherry Point Rd, James City

C-27 De Bretigny | 1011 Pollock Street

C-30 F.M. Simmons | 417 East Front Street

C-33 James Walker Hood | 432 George Street

C-39 Political Duel | 411 Johnson Street

C-42 Christ Church | 320 Pollock Street

C-50 First Provincial Congress | 308 Broad Street

C-51 Batchelder's Creek | NC 55 West of New Bern

C-53 George White | 406 Metcalf Street

C-60 Caleb Bradham | 327 Pollock Street

C-61 New Bern Academy | 500 Hancock Street

C-64 James City | Hwy 70 East of New Bern

C-66 Rains Brothers | 605 East Front Street

C-67 USRC Diligence |200 South Front Street

C-70 Bayard Wootten | 519 East Front Street

C-74 Graham A. Barden | 298 Broad Street

C-80 Andrew's Chapel | 400 Broad Street

C-81 King Solomon's Lodge | 710 Howard Street

C-82 Samuel Cornell | 400 East Front Street

C-84 First North Carolina Colored Volunteers| 514 New Street

CC-1 Battle of New Bern | 424 East Front Street

CC-2 Battle of New Bern | US 70 East at the Battlefield Park