Giving Thanks in the Midst of War

by Claudia Houston, Historian, New Bern Historical Society

During November our thoughts often turn to family, food and home in preparation for Thanksgiving. Although we often associate the story of the Pilgrims’ first Thanksgiving with this celebration, Thanksgiving has strong roots in the Civil War.

Through the years, many of our leaders have asked that a day be set aside to express our thankfulness. The Continental Congress during the Revolutionary War asked that days be dedicated to give thanks, and in 1789 George Washington issued a proclamation of thanks during the first year of his presidency. Presidents John Adams and James Madison issued proclamations as well.

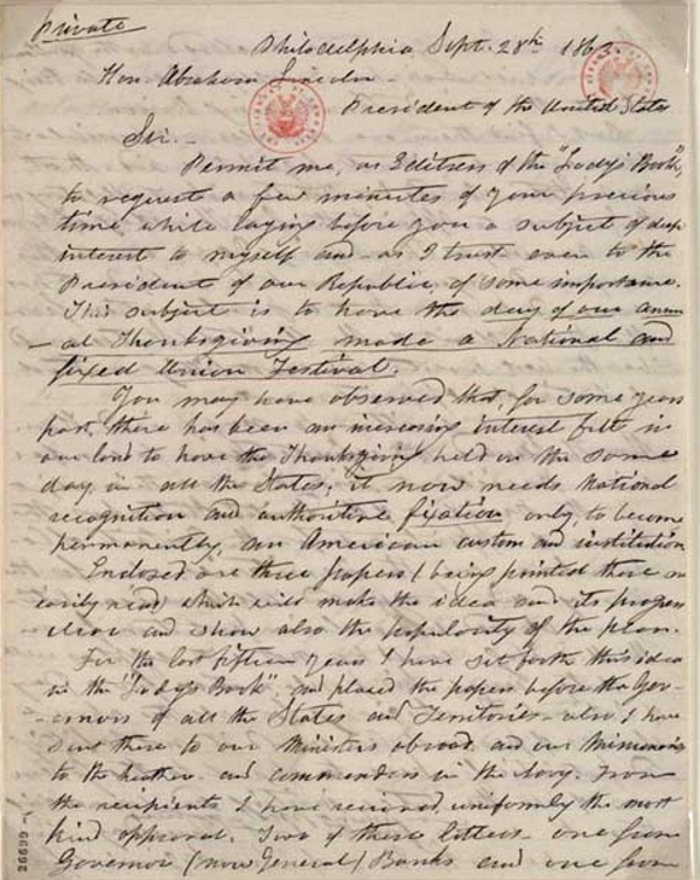

During the Civil War, the Thanksgiving holiday was a cultural tradition celebrated locally by communities in different regions of the United States. Both the Union and the Confederate Armies held periodic and separate days of thanksgiving in response to military victories. Confederate President Jefferson Davis called for a “day of fasting, humiliation and prayer” to take place on November 15, 1861. Sarah Josepha Hale, editor of a popular women’s magazine, lobbied President Abraham Lincoln to establish a national day of Thanksgiving as an attempt to unify a nation that was strongly divided along many lines.

On October 3, 1863 Lincoln issued a Thanksgiving Day Proclamation that was written by Secretary of State William Seward. Despite the strife of the war, Lincoln’s hopeful message adjured Americans to celebrate a “year filled with the blessings of fruitful fields and healthful skies.” On November 26, 1863, President Lincoln held the first official Thanksgiving Day celebration.

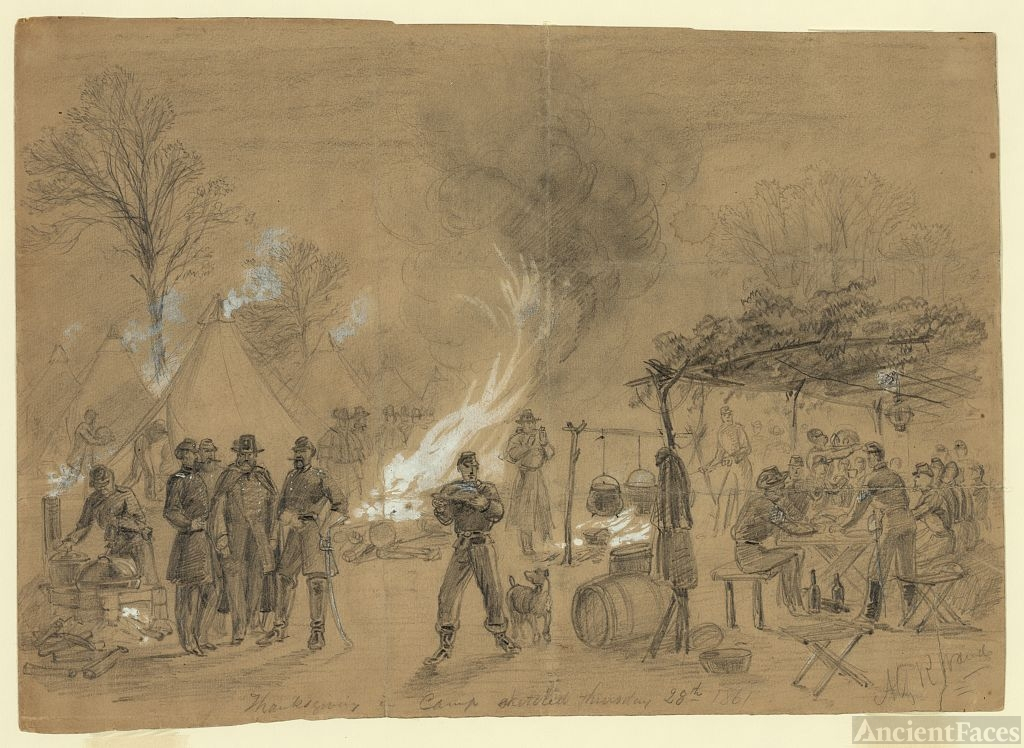

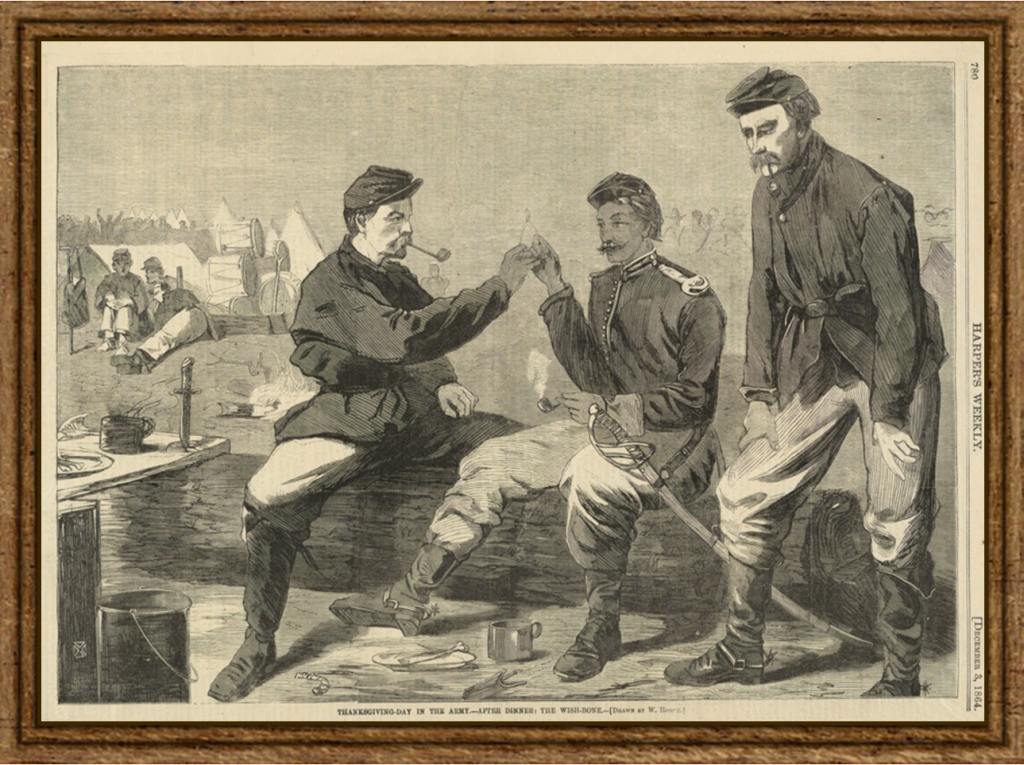

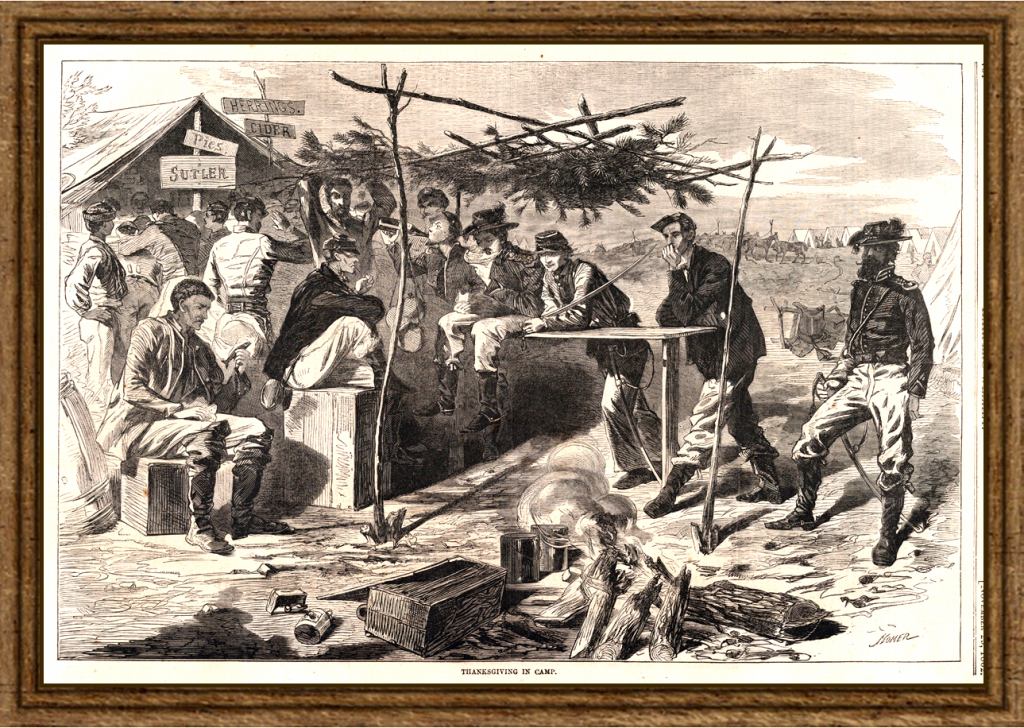

How did the troops celebrate during the war? For many southerners, this was a day like all the rest. Many refused to celebrate as they viewed Thanksgiving as a New England abolitionist holiday. For the Union troops the response was a bit different. Many remembered past Thanksgivings surrounded by family and loved ones. In 1862, Edward J. Bartlett of Concord, Massachusetts, age 19, enlisted in the 44th Massachusetts Infantry, Company F and was stationed at New Bern. He wrote letters home in 1862 describing his first Thanksgiving as a soldier. There were elaborate preparations, decorations, and food:

“First we had oysters then turkey and chicken pie then plum pudding then apple raisin & coffee with plenty of good soft bread & butter. After we had all eaten a little too much, people usualy [sic] do on Thanksgiving days and we who had lived so long on hard tack did our best[,] we had a fine sing.” (Massachusetts Historical Society)

Writing home a year later from Nashville, Tennessee, Bartlett's letter reflected his growing despondency:

“Our company Thanksgiving in the barracks last year is a day that I can never forget. Six of those boys are now dead. Poor Hopkinson, the president, in his address, [said] ‘that he hoped the next year would see us all at our own family tables.’ He died two months after.”

Bartlett spent his third Thanksgiving at war stationed at Point Lookout, Maryland, guarding Confederate prisoners-of-war. He wrote in 1864 to his sister Martha of his homesickness on the evening before the holiday:

“Thanksgiving eve. I sat over the fire, thinking of what you were doing at home, and what I had done on all the Thanksgiving eves, that I could remember.”

In the darkest days of our history, with thousands of men dying on battlefields far from home, during wartime or peace, Americans still paused and give thanks for what we have. May we honor them by continuing to do so.

With gratitude for your support, a Happy Thanksgiving from your New Bern Historical Society family!