High Hopes and Steadfast Belief

by Claudia Houston, Historian, New Bern Historical Society

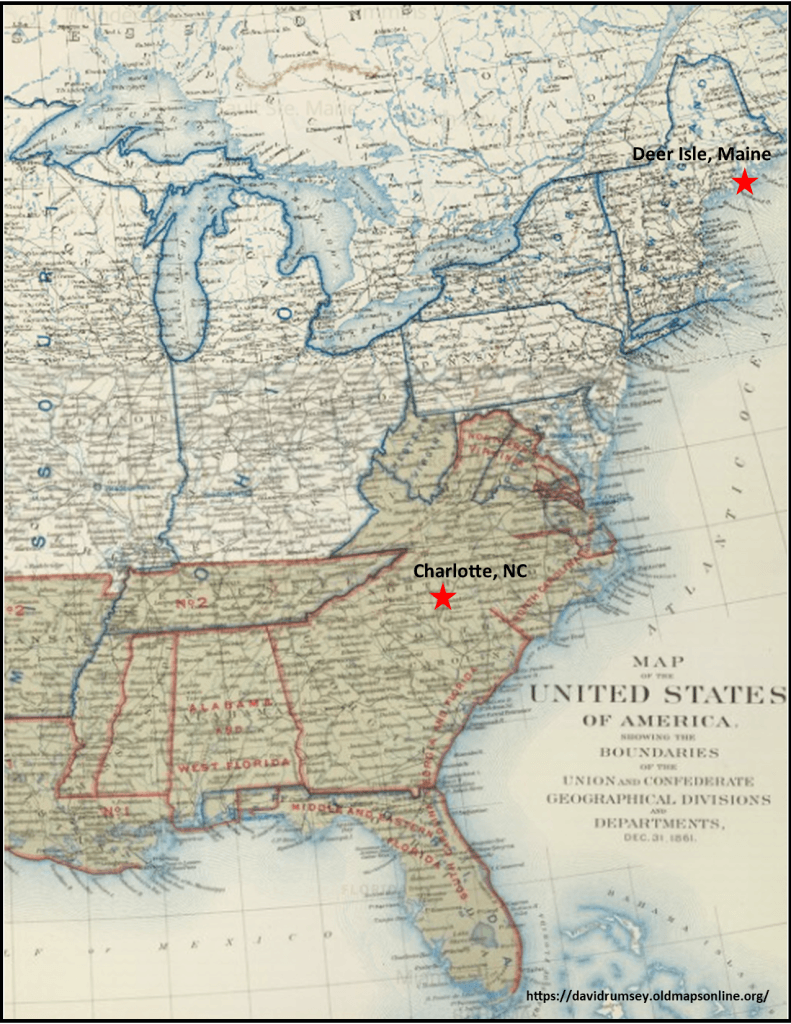

At the start of the Civil War in 1861, the small towns of Deer Isle, Maine and Charlotte, North Carolina were about as far apart geographically, ideologically, and socioeconomically as they could be. Situated 1088 miles apart, it is doubtful that the folks of either town had ever heard of the other. Their futures were even more divergent. Today Charlotte is now the largest city in North Carolina with a population approaching one million, while tiny Deer Isle is even smaller than it was in 1861.

So, what do these places have in common? They both sent many of their native sons to fight in the Civil War, and each town had at least one soldier who fought at the Battle of New Bern. This is the story of two of those men.

Deer Isle, Maine, population 3600, was a large fishing village consisting of 26,000 acres of islands. Isolated but tightly knit, everyone knew one another and nearly all were connected in some way to the fishing trade. It was also very cold for most of the year. Snow - and lots of it - was common even in April.

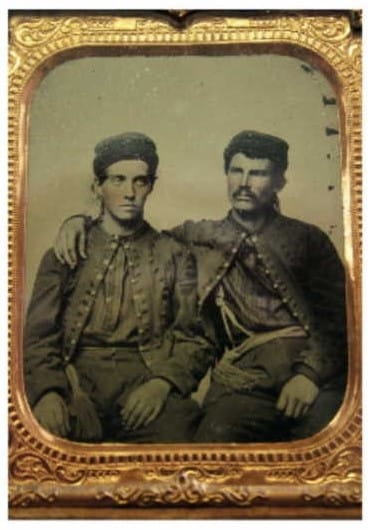

Charles Harris Gray and his father, Captain Joseph Gray, were fishermen. Charles, age 27, had been fishing since he was a young boy. A popular man, he and his family were known by everyone. Charles was on a fishing schooner at Gloucester, Massachusetts when he heard that Fort Sumter had been fired upon and war had been declared. Deer Isle was in shock at the news and speculated about whether the approximately 600 men between the ages of 17 and 35 would be called upon to fight. To Charles, this decision was easy. On April 15, 1861, he enlisted for three months in the 8th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment which was just being formed.

Charles Gray served his three months and came home. He did not participate in any battles and ended his military service in Boston. His mother, however, was frantic with worry the entire time he was away and when Charles spoke of reenlisting, she made him promise that he would not do so. As others from the town began enlisting, Charles became more and more restless. He had a difficult time staying home while others were leaving to fight and decided to ship out on a local fishing schooner. He arrived in Boston just as the 23rd Massachusetts Infantry regiment was being formed. On August 27, 1861, despite his promise to his mother, Charles enlisted in Company A. He knew his mother would be worried if she knew what he had done, so he listed his sister Sarah’s husband John Webster as next of kin.

In March 1862 John Webster received a letter from an undetermined source. The handwriting was not familiar and he knew it was not from Charles. When he opened this envelope, he discovered the letter was from E.A.P. Brewster, commander of Company A, 23rd Massachusetts. The first line told it all. “It is with pain that I have to announce to you the death of your brother, Charles Gray.” Included with the letter was an announcement that the commanding officer indicated could be sent to a newspaper if so chosen.

Died,

At the battle of Newburn, March 14th.

Corp. Charles Gray of Co. A, 23rd Reg. Mass Vol.

He was shot through the body while in action and died immediately. His last words were, “We will never give up.” A few minutes before, he had borne off in his arms, his wounded companion, through the thickest of fire. He returned to fall himself. He rests with many others, beneath the hard-won soil of North Carolina.

His sister, Sarah, ran home to tell her mother the terrible news. The entire town was stunned. Charles had been the first in Deer Isle to enlist in the war and now was the first to be killed. When his personal effects were eventually sent home via mail, they included his hat, a certificate citing his promotion to Corporal, and a small wooden cartridge box. The family was horrified to learn that the box contained the bullet that killed Charles. His mother refused to look at it and eventually one of his sisters put it in the attic of her home where it remained forgotten for many years.

After the end of the war the family was in mourning once more as their younger daughter, Hattie had just died. But then a friend of Charles, Joseph Addison Payne, came to visit the family. He explained that Charles lost his life carrying Payne from the field after he had been shot. Payne broke down and cried at the first mention of Charles’ name. “I wouldn’t be here today and perhaps he would be” he said sorrowfully. He carried that burden until the end of his days. To make matters worse for the family, the body of Charles Harris Gray was never located. He most likely was buried initially where he fell on the battlefield but according to one source, his body was moved three times. A cenotaph stands at Forest Hill Cemetery in Deer Isle to commemorate the deaths of Charles and his sister Hattie.

And now to 1861 Charlotte, North Carolina. Situated in Mecklenburg County, tiny Charlotte boasted a population of only 2,265. There Hugh Ewart McCaulay, one of eleven children born to Hugh L. McAulay and Nancy Davidson Alexander, lived with his parents. Like most everyone else in Charlotte, the family farmed and sold crops and animals.

Many men from the Mecklenburg County/Charlotte area enlisted in the Confederacy. In September 1861, 21-year-old Hugh enlisted as a private with Captain Owen N. Brown's Company C. Known as the “Mecklenburg Wide Awakes,” they were part of the 37th North Carolina Infantry.

Hugh and his unit participated in the Battle of New Bern which took place on March 14, 1862. The 37th NC acquitted itself well, but in danger of being outflanked, the unit burned its baggage and retreated towards Kinston. One man was killed, six men were wounded and two were missing after the fight. The Confederate troops were defeated and New Bern came under Union occupation for the rest of the war.

Hugh and his unit participated in the Battle of New Bern which took place on March 14, 1862. The 37th NC acquitted itself well, but in danger of being outflanked, the unit burned its baggage and retreated towards Kinston. One man was killed, six men were wounded and two were missing after the fight. The Confederate troops were defeated and New Bern came under Union occupation for the rest of the war.

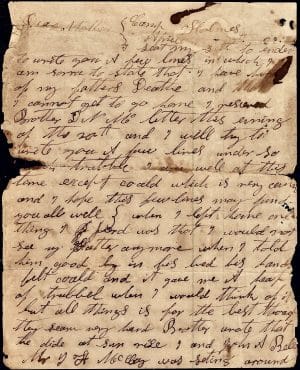

Hugh wrote a letter home to his sister, Nancy McAulay on April 13, 1862, from Camp Holmes in Kinston. He talked about the war but, being a farmer at heart, he also spent a lot of time talking about the soil, declaring that while it was not good for peaches, he saw more cotton on one farm than he had seen in all of Mecklenburg. He wrote, “In the field where I was put up, it would be a good place to live if the war was over but Old Mecklenburg is the best place yet for me and I do hope to get home sometime this summer to walk around the yard and in the garden among the flowers and talk about old times and talk about the war.’

Hugh and the 37th NC went on to participate in battles at Hanover Court House, Virginia, Malvern Hill, and 2nd Manassas, among others. In April, he learned that his father, Hugh L. McAulay had died at the age of 65. He asked for a furlough to be able to go home but the Colonel denied it and Hugh declared “I may just settle myself to stay until the war is over or there is a change of affairs.”

By May, Hugh was quite ill and hospitalized at General Hospital No. 1 in Lynchburg, Virginia. He was declared dead on May 24, 1862, having served for eight months. Cause of death was “febris typhoides” or typhoid fever. (Note, a second source said he died at Warwick House hospital near Richmond.) Hugh E. McAulay was buried at Hollywood Cemetery, Richmond.

Although on opposing sides of the war, Charles Gray and Hugh McAulay both enlisted with high hopes and a steadfast belief in their cause. While their paths would not ordinarily have crossed, their fates came together in March 1862 when they fought against each other in yet another small town, New Bern, North Carolina. Both were far from home and neither body was returned home for burial, but their families, their communities, and we, still remember them.

Author's note:

Charles Gray and the Civil War story of Deer Isle, Maine, was featured in the Ken Burns PBS documentary of the Civil War. If you want additional information, the story of Charles Gray along with others is included in the book, “A Maine Town in the Civil War” by Vernal Hutchinson 1957, Deer Isle Historical Society. The artifacts presented in this story are at the Deer Isle-Stonington Historical Society. For information, check out https://www.dishistoricalsociety.org/.

Letters from Hugh McAulay to his sister are from the website “Spared and Shared” at https://sparedshared14.wordpress.com/2017/01/09/13-april-1862/ Hugh’s brother, Private Daniel Neal McAulay, was also in the 37th NC and he died in 1865 in Petersburgh, Virginia. He is buried at the Gilead ARP Church in Huntersville, Mecklenburg County, NC near his parents. Another brother, Ephraim, also enlisted in the 37th NC, was captured near Petersburgh, and confined at Point Lookout Maryland. He was confined until released on June 29, 1865, after signing the oath of allegiance.

signing the oath of allegiance.

For more stories like this from New Bern’s past, be sure to visit the Duffy Gallery at the North Carolina History Center to see our free centennial exhibit, “Through the Looking Glass, A Journey with the Storytellers.”